Why People Don’t Always Act Rationally with Money

- Daria Kozhukhareva

- Sep 3, 2025

- 4 min read

Cognitive biases that drive everyday financial decisions — from anchoring to loss aversion.

“Nothing in life is as important as you think it is, while you are thinking about it.” — Daniel Kahneman

Money seems straightforward — earn it, save it, spend it. But the reality is more complicated. Our brains are wired to use shortcuts, emotions, and social influences that often lead us to make financial decisions that don’t seem rational. Behavioral economics, especially the work of Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler “Thinking, Fast and Slow”, explains these predictable quirks of human behavior.

Mental Shortcuts and Anchoring: The “Wolf of Wall Street” Effect

Anchoring is a mental shortcut where the first piece of information acts like a mental “anchor” that distorts later judgments. For example, when you see a jacket originally priced at $200 but now selling for $120, your brain anchors on $200 and perceives $120 as a bargain, even if the jacket’s true value is much less than even these $120.

This mechanism doesn’t just apply to shopping. Investors frequently anchor on the price at which they bought stocks, leading them to irrationally hold onto losing investments because selling below their purchase price feels like admitting a loss. Kahneman showed that anchoring occurs unconsciously, making it hard to avoid without active awareness. In “The Wolf of Wall Street”, Jordan Belfort uses anchoring tactics to inflate stock prices artificially and manipulate clients into buying worthless shares — a dramatic but real-world example of how powerful anchoring can be.

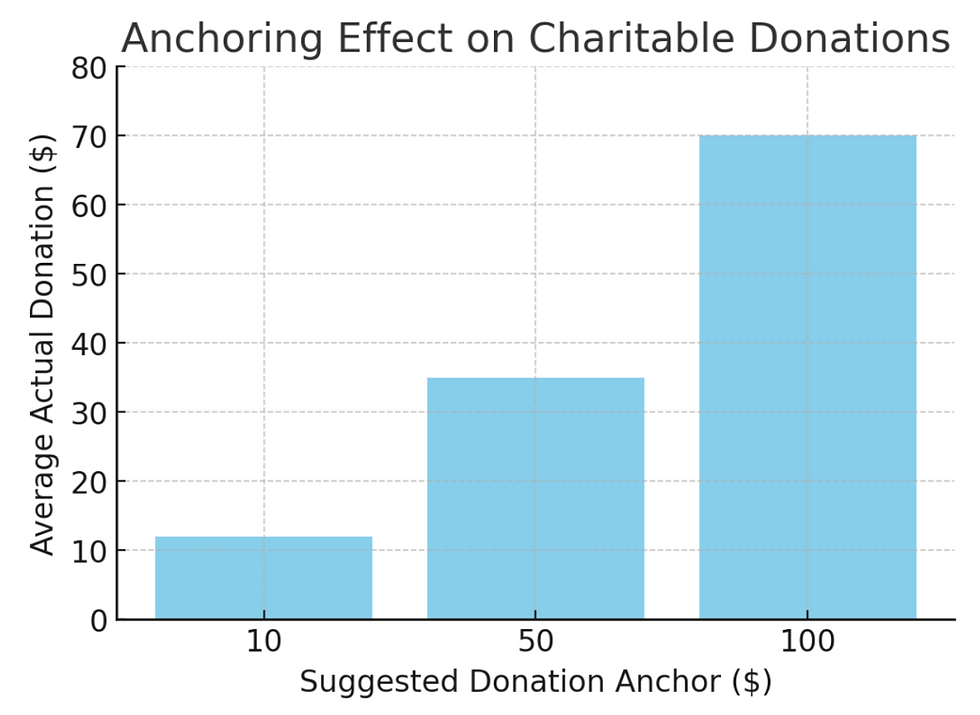

Additional research indicates anchoring affects salary negotiations, price expectations, and even charitable giving. This bar chart shows how the average donation amount increases with higher suggested anchors: with a $10 anchor, the average donation is $12; with $50, it rises to $35; and with $100, it reaches $70. This is a classic example of how the first number we see influences our decisions. Our brains fixate on initial values, often against our financial best interest.

Loss Aversion: Why Losing Feels Like a Punch to the Gut — While Gaining Feels Like a Gentle Pat on the Back

Kahneman and Tversky’s prospect theory revealed a fascinating insight: people experience the pain of losses about twice as intensely as the pleasure from equivalent gains. But why is this?

The answer lies in our evolutionary history. Early humans faced immediate survival threats where losses — such as losing food, shelter, or safety — could mean death, while gains, though beneficial, were less urgent. This survival wiring made our brains highly sensitive to losses as a protective mechanism. In today’s financial world, this ancient wiring still dominates. Losing money triggers a stronger emotional reaction than gaining money. This asymmetry leads many to avoid risks, hold on to losing stocks hoping to break even, or hesitate to make necessary changes — even when such changes could improve outcomes.

In the film Moneyball, baseball executives resist innovative strategies because the fear of losing established ways outweighs the excitement of potential gains. Similarly, consumers may avoid sales if they fear wasting time or effort more than they value the discount. This evolutionary bias, while once lifesaving, now causes missed financial opportunities and suboptimal decisions in the world of compound interest, investments, and economic growth.

Emotional Spending: When Your Wallet Is in the Mood

Money decisions are rarely purely rational. Emotions deeply influence our spending habits. Stress, sadness, or boredom often lead to emotional spending — impulse buys intended to boost mood temporarily.

Pixar’s Inside Out beautifully illustrates how emotions can override logic. Psychologists confirm that such spending may temporarily relieve negative feelings but can lead to buyer’s remorse and financial strain. Research shows consumers tend to spend more during emotional highs or lows and less when emotionally neutral. Advertisers capitalize on this by linking products with emotional benefits. Understanding emotional triggers is essential for improving financial health. Practicing mindfulness and building spending pauses can help curb emotional impulses.

Herd Mentality and Overconfidence: Lessons from The Big Short

Humans are social animals who often follow the crowd. This herd mentality drives phenomena like market bubbles and crashes. The 2008 financial crisis, vividly depicted in The Big Short, shows how investors collectively ignored warning signs, swept up by the group’s momentum. Simultaneously, overconfidence — the belief in one’s superior knowledge or skill — leads many to take risky bets or disregard expert advice. Overconfidence biases inflate self-assessment, encouraging poor financial decisions.

These social and thinking mistakes combine, making financial ups and downs worse and causing bigger losses for people.

Mental Accounting: The Tax Refund Splurge

Richard Thaler’s concept of mental accounting explains why people treat money differently depending on its source or intended use, despite all money being fungible. For instance, people often splurge tax refunds on luxuries but budget tightly on regular income. Similarly, credit card spending feels less “real” than cash, increasing expenditure. You don’t feel how much you spend by attaching a credit card to a terminal. Mental accounting can lead to irrational spending and saving behaviors, undermining financial goals. Studies highlight that awareness of mental accounting helps individuals reframe money perceptions, improving budgeting and savings discipline.

Overconsumption and Social Trends: The Stanley Thermos Craze

Social media and influencer culture drive waves of overconsumption. Products like Stanley thermoses or trendy water bottles become status symbols, prompting purchases to fit in or appear trendy—even if the buyer doesn’t need them. This behavior is fueled by social proof and identity signaling — we buy to belong and express identity. Research shows these social influences often outweigh practical needs in consumer decisions. The result is clutter, wasted money, and buyer’s remorse, perpetuated by relentless marketing and peer pressure.

How to Outsmart Your Brain and Trends

Awareness is key. Pausing before purchases, focusing on personal financial goals, tracking spending honestly, and questioning social pressures help regain control.

Research suggests a 24-hour delay on non-essential purchases reduces impulse buying. Defining values and budgeting with mindfulness counteracts mental accounting distortions and herd influence.

Sources

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Thaler, R. H. (2015). Misbehaving.

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably Irrational.

Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion.

Dittmar, H., et al. (2014). Materialism and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Research articles on mental accounting and impulsive buying from Journal of Consumer Research and Marketing Science.

Films: Inside Out (2015), The Big Short (2015), Moneyball (2011), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013).

.png)

Comments