Peto’s Paradox: Why Larger Organisms Have Better Cancer Suppression

- Haani Hilmy

- Nov 26, 2025

- 4 min read

More often than not, we tend to associate larger body sizes with being more susceptible to cancer. This idea is amplified due to the presence of more cells in species with larger body sizes, such as whales and elephants. However, this is not truly the case.

Peto’s Paradox, first proposed by English statistician and epidemiologist Richard Peto, describes the inverse correlation between body size and the number of cells of an organism at the species level and the incidence of cancer. For example, organisms like whales have a much lower risk of carcinogenesis than humans, despite having 1000 times the number of cells. It is for this very reason that Peto’s discovery was labelled a paradox. While there is no one explanation that solves the paradox, scientists continue to discover how different animals overcome their risk of carcinogenesis.

To understand Peto’s Paradox at a deeper level, one must first understand the methods of cancer suppression at the molecular gene level. Cancer suppression is possible via a plethora of processes, such as DNA repair systems controlled by enzymes, cell senescence, and apoptosis.

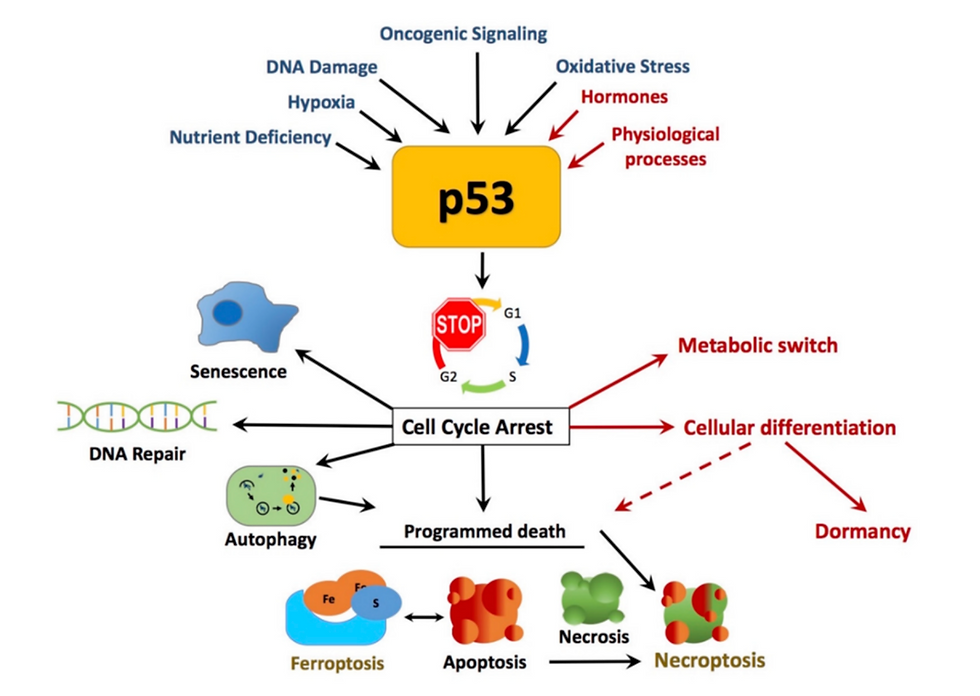

DNA repair systems involve the action of enzymes that “repair” mutations in genes through mechanisms such as Base Excision Repair (BER), where multiple enzymes, such as DNA glycosylase, identify and remove bases in the codons, resulting in the mutation being eliminated while the gene sustains little to no damage. Moreover, processes such as cell senescence involve the complete and permanent halting of mitosis in faulty cells, while apoptosis results in the destruction of faulty cells to prevent their development into cancer cells. At the heart of all this lie the tumor suppressor genes, which quietly yet systematically regulate the incidence of cancer in organisms, especially the TP53 gene. The TP53 gene, infamous for its suppressive action, codes for the protein p53, responsible for the triggering and regulation of the processes explained above.

A representation of how the TP53 gene functions to bring about cancer suppression (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325657277/figure/fig1/AS:11431281210526110@1702048625000/p53-canonical-and-non-canonical-tumor-suppressor-roles-of-p53-p53-is-activated-by-a.tif)

Solutions to Peto’s Paradox

The Elephant is a prime example of how effective the TP53 gene can be for the suppression of tumors. As explained previously, when genes are damaged, the TP53 gene activates the pathway for apoptosis via the p53 protein. Because the elephant’s cells contain 40 alleles of additional TP53 allele copies, the likelihood of apoptosis when genes are exposed to carcinogens occurring will increase, resulting in a much lower incidence of cancer.

Whales, on the other hand, although having several duplicates of the TP53 gene, with fewer compared to the elephant, experience such sparse risks of cancer as they have evolved to have enhanced versions of the TP53 gene. As per studies conducted in 2018, it has been revealed that certain loci present in the genome of the humpback whale have shown evolution at a faster rate than in other mammals. These loci, responsible for the regulation of the cell cycle, proliferation, and DNA repair, have shown increased efficiency due to the success of evolution. This has also led to better maintenance of telomeres, preventing cells from dividing uncontrollably. Furthermore, this has also led to hypersensitivity to apoptosis in whale somatic cells so that almost any possibility of carcinogenesis is eliminated early on.

Perhaps a factor that contributes to the rare presence of cancer in large organisms such as the whale and elephant could be the fact that they have slower metabolic rates. This would mean that mutagenic agents present in the DNA of such organisms are simply fueled at higher rates in smaller animals that are not present in these organisms. This would also result in a slower mutation rate, as it would mean a slower rate of cell division. Further, the slower metabolic rates would also lead to a reduction in the release of DNA-damaging byproducts such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), which may cause gene mutation.

A graphical representation of cancer incidence (equivalent to estimated mutation rate given in Y-axis) by number of cells of the body (implied by X-axis) (https://royalsocietypublishing.org/cms/asset/9300dd09-a4d2-460a-9305-edef3dd0e538/rstb20140222f02.jpg)

Possible Research Developments

Furthering research on Peto’s Paradox can immensely benefit humans. Possible research areas could include the introduction of several more active TP53 genes in order to investigate their effect on the human cell, directing research toward gene therapy where pH3 activity is enhanced in a method that does not cause disproportionate cell death. In addition, studying how Peto’s Paradox is solved in more animals could lead to improvements in anti-aging and longevity research, as such organisms can maintain telomere length, low oxidative stress, stable DNA and protein structure, all of which are factors crucial to carcinogenesis in organisms.

Reference List

Clinic, C. (2023). Tumor Suppressor Genes: Types & Function. [online] Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24833-tumor-suppressor-genes .

Cohut, M. (2019). Why don’t whales develop cancer, and why should we care? [online] Medicalnewstoday.com. Available at: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/325178.

Cooper, G.M. (2025). Tumor Suppressor Genes. [online] Nih.gov. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9894/.

Tollis, M., Boddy, A.M. and Maley, C.C. (2017). Peto’s Paradox: how has evolution solved the problem of cancer prevention? BMC Biology, [online] 15(1), pp.60–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-017-0401-7.

.png)

Comments